|

|||

|

|

|||

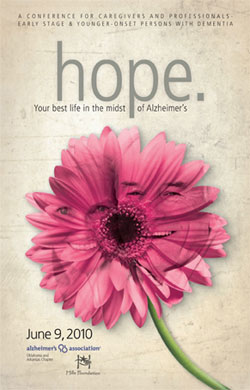

| JUNE 09, 2010

ALZHEIMER’S SPEECH/TULSA There are no hidden lessons in the Alzheimer’s journey. It is long and slow and awful and when at last the victim dies the autopsy reveals that her brain was riddled with dead neurons. She was, in fact, not there at all. She was a blank slate, an ellipsis, a zero. The family, having crawled through these trenches together for nine years, does not do well. Everyone is exhausted, relationships are strained to the breaking point, brothers are furious with brothers and sisters grow rigid with repressed sorrow. Silences bristle with recrimination and the house that once represented solace is now full of doubt. Despair is at the ready, grief is held in abeyance, the body of the loved one is laid out in all its ignoble glory, and a decade has passed without laughter. I remember sitting at the kitchen table after a particularly messy family conclave and thinking, who will be left standing when the smoke clears? Such heavy costs this disease exacts. So many are wounded and some never recover at all. Most people find it extremely hard to bear witness to this disease because it is so insidious. It is not grand in its cruelty, it does not elicit immediate sympathy. It is like a very clever magic show, done with smoke and mirrors. Now you see it, now you don’t. The lovely person once so central to your own happiness disappears into the wings and enters from the other side, someone else entirely. This is the diabolical kick. It is enough that we must struggle with the brevity and frailty of the human condition every day of our lives – it is almost too much to bear, this business of watching one of our most cherished disappear into oblivion. No good-byes, no nothing. Just the final ticking of imposed rituals, the burial, the silence. Eyelids are closed over long dead eyes and everyone waits for the collective sigh of relief. But it doesn’t come. Brothers storm out of the house, sisters pack up, someone is sneaking another drink, someone is stealing a photograph, the oldest daughter prepares a last meal. In the room where my mother is laid out in the coffin my brother shaped, the caregiver sits in silence. She is a little woman and she comes from a faraway place called Campeche, Mexico. She has been legally married twice, has given birth five times and one night she sat with her eleven siblings and they drew straws to determine who would slip across the border with a coyote and start a new life in America. She drew the short straw. Her name is Lucy and she was my mother’s caregiver. She had been my children’s nanny for many years and when I told her that my mother had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s she said, “I’ll go, Senora. I want to go.” And so she left Los Angeles, bade her children and grandchildren good-bye, told her husband to come if he wanted, and got on a plane with me to Dubuque, Iowa. She got two for the price of one. My father sat on the couch, legs crossed, coffee on the side table, cigarettes at the ready, crossword puzzle in hand. When I introduced him to Lucy, he slowly shook his head and said, “I don’t know what the hell you’re doing here, sweetheart, but you won’t be here long.” My mother, in the early stages of the disease, thought Lucy had come for dinner and puttered around trying to assemble a meal. Lucy suggested they make it together. When dinner was over, my mother announced that she and Lucy were going for a private walk, just to get certain things straight. She took Lucy into the front yard and said, “They’ve stolen my car keys and they’ve hidden my car. I want you to find my car keys, don’t tell anyone, and then we’ll split a beer.” Lucy assured her that everything would be all right, and so they split the first of many beers. My father was tough in his obduracy, but my mother was tougher in her passion. Lucy walked into the middle of this battle of wills, looked long at my father, made him a perfect enchilada, poured him a drink, and took my mother’s hand. She didn’t let go of that hand for nine years and in those nine years wove a thread of grace through the madness, lacing everything with gentleness, restoring a sense of peace and dignity. When my mother became agitated and would not be comforted, Lucy ran her a hot bath and filled the tub with perfumed bubbles. She had music wired into the bathroom and played Puccini every night for my mother as she sat in her tub. Slowly, slowly, my mother would let go and soon she grew still as Lucy bathed her with a soft cloth, in warm water, to Maria Callas hitting a perfect high C. The rituals were exercised with regularity but Lucy had added a note of mystery and charm to almost every aspect of my mother’s day. The meals were not just meals but small celebrations of the day. Lucy studied my mother as one would a difficult but very special child. By the process of trial and error, she learned what pleased my mother and what didn’t. She watched carefully and developed a heightened sensitivity to my mother’s changing moods, instinctively knowing when agitation was exhaustion, when too much stillness was fear, when twitching and plucking signified confusion and anxiety. She moved my mother’s bed from her upstairs room to the living room downstairs and when we suggested a hospital bed, Lucy stiffened in resistance. No, my mother’s bed, the bed she was to spend the last years of her life in, was a thing of beauty. Lucy bought crisp white sheets and found an eiderdown quilt that my mother appeared to adore. She spent days until she was satisfied with the pillows and when I questioned her said, “But, senora, her head is full of bad things, she needs to lie down and smell good and feel good and especially the pillow must be not too soft, so she does not sink.” Lucy approached her work with the discipline and deep vitality of an artist. She was no saint, certainly, and this is why she understood my mother so well. Lucy understood that my mother had tried to be fully human, had made a singular effort to be excellent in her life, and Lucy recognized that essence and treated my mother with great and unflagging respect. This capacity to respect the afflicted was perhaps her greatest gift and in it lay the source of her strength. She was honored to care for my mother, and she drew from my mother’s character a sense of integrity, endurance and whimsy. She held these qualities up to my mother as a reminder of who she once was and never once, in all the unrelenting loneliness of this service, did she succumb to smallness. She grew tired and frustrated, of course, and she struggled daily with an encroaching sadness because one of the great perils of care giving is falling in love. As she fed my mother and bathed her and changed her diapers, as she steadied her when she stumbled and brushed her silver hair, as she sang to her and my mother sang back, snatches of a girlhood song, as she walked with my mother and linked arms and strolled down the lane at sunset picking flowers, looking at cloudscapes, slipping a feather into my mother’s sleeve, as she sat with my mother for hours in the dark night and calmed her terror, when she cleaned her dentures and cleaned her bottom and washed her feet and made her bed and sat in the armchair and watched my mother as she stared at the ceiling, Lucy fell in love. Now, we all know that the Alzheimer’s victim is cognizant of nothing at the end – not who she is or why she is or what she is. We all know that this disease closes up the lovely house, as one by one the lights go out. We all know that we want it to end quickly and that it won’t and that there is nothing to do but wait it out. In my experience, and although we loved her beyond words, none of my siblings or even myself were capable of caring for my mother in the way she deserved. We lacked the patience, the forbearance, the serenity and the acceptance to travel this crooked path with any grace. Caregiving is a gift and it comes from somewhere deep inside. It is a pride of place, a confidence, a lightness of touch, a soulfulness. It is fiercely loyal, and tender, and exacting. Good caregivers are great soldiers, unafraid of uncharted waters, intrepid in their devotion, markedly brave and usually very bossy. Lucy had to be bossy to fight her way through so many of my mother’s children and their sorrows and their demands and their issues and their sense of entitlement. But fight she did and in so doing, she gave my mother her rightful passage to death. She pushed us all aside and said, “It is time for your mother to die. We must get ready.” When my mother died, we decided to honor the old Irish custom of bringing the casket into the house. My youngest brother built the coffin and all of my brothers placed my mother in it and we filled the room with flowers and candlelight. One by one, we slipped into the room and said good-bye. At the end of the day, I prepared a meal and as I cooked I watched through the door as Lucy quietly slipped into the mourning room and knelt before my mother. She leaned forward as if expecting something, her eyes were shining, and she gazed at my mother with a look I had never seen before. It was completely alive, it was completely present, it was ardent and overwhelmed at the same time and then, of course, I knew. It was the look of someone who had given great care and, in so doing, had found great love. Lucy stood up, bent over, and kissed my mother on the lips. I saw her slip a rosary around my mother’s wrist, which would have been a bone of contention with my mother but since she could no longer argue, Lucy took advantage of the moment and putting her mouth next to my mother’s ear whispered, “Adios, mi amor. Vaya con dios.” Today, as I look around this room, I know that everyone here has been somehow affected by this disease. You are husbands and wives, you are doctors and scientists, you are sons and daughters, you are friends and volunteers. You are caregivers. And to the caregivers I want to say: never doubt for one moment the power and beauty and importance of your service. When you are tired and sad and overwhelmed, find someone who will spell you for a few hours and take a walk and breathe deeply and understand that you are crucial and that this gift, masquerading as a burden, sets you above the rest. Be very still and you will hear Lucy’s voice and it is saying, ”Vaya con dios.” And I say persevere-you are the elect. You are showing us the way. |