Carnivorous Plants Story

Picture book for a young audience /

Kindle Edition

by

Makoto Honda

Copyright (c) 2013-2017 by Makoto Honda.

All Rights Reserved.

_______

Venus Flytrap

GENUS Dionaea

The Venus flytrap grows in the coastal savanna of North and South Carolina in the United States. This is the only region in the world where the Venus flytraps occur naturally. The botanical name of the plant is Dionaea muscipula. The plants typically grow on the bed of sphagnum moss or on the surface of moist sand in a savanna sparsely populated with trees.

The

natural habitat of the Venus flytrap, in May, in North Carolina. The plant grows

in a moist sandy soil in a pine forest. The Venus flytrap is a sun lover, and

grows best in a sunny locale. Note a small flower stalk just emerging from the

rosette center. Accompanying carnivorous plants include sundews, terrestrial

bladderworts, and some pitcher plants.

Traps of

Venus flytrap plants growing in North Carolina, in July. Note the trap in front

is tightly sealed, indicating the digestion of the victim is well underway.

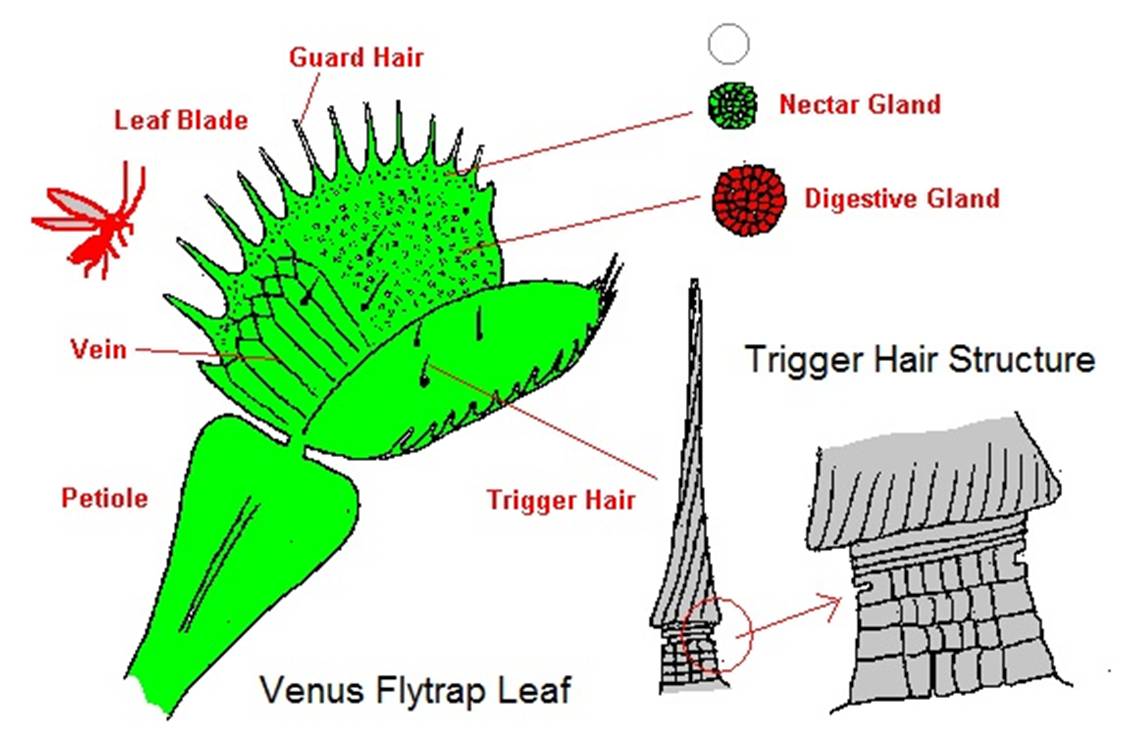

The Venus flytrap uses a snap-trap, considered by many botanists to be the most advanced of all trapping mechanisms used by carnivorous plants. The trap portion of the leaf consists of two clamshell-like lobes connected along the midrib. Around the margin of each lobe grow stiff, spine-like guard hairs. Along the edge of each lobe, just below the guard hairs, runs a band of nectar glands that produce a sugary substance. This is an attractant to lure potential prey to this deadly trap. Much of the inner lobe below is covered with hundreds of digestive glands, which often paint the trap with a brilliant red color. On the inner surface of each lobe are three tiny hairs. These are called trigger hairs and are sensitive to stimulation.

A leaf of

the Venus flytrap. Note three tiny hairs growing in a triangular position on

each lobe surface. These are sensitive hairs that trigger trap closure.

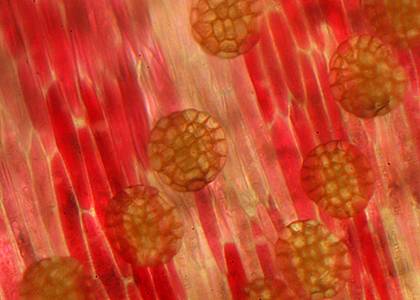

Digestive

glands covering the inner lobe surface of the trap. These glands are often

colored red, which create a visual attraction for unwary prey. These glands

produce digestive juices when the prey is captured.

A trigger

hair growing on the inner surface of the trap lobe. There are three hairs on

each lobe surface. These hairs are sensitive to stimulation. When an insect

brushes these hairs, the trap snaps shut, entrapping the prey between the two

lobes.

A leaf of the Venus flytrap consists of a petiole (leaf stem) and a leaf blade that is modified to function as a snap-trap. The trap is composed of two semi-circular lobes connected along the midrib. The free margin of the lobe is lined with stiff spines, or guard hairs. There are two pairs of three tiny bristles on the lobe surface. These are trigger hairs which are sensitive to stimulation.

Glands on

the surface of the trap lobes.

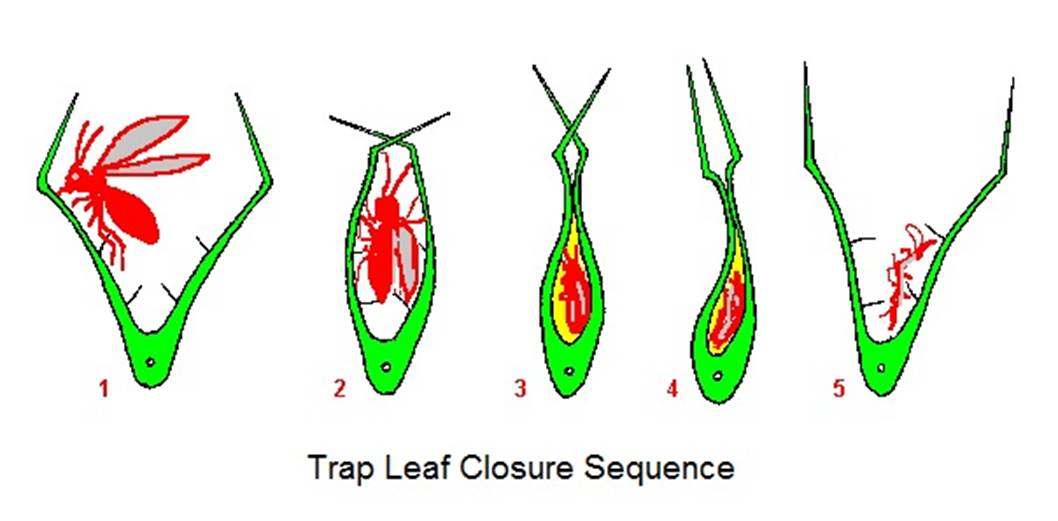

When an unwary insect brushes these hairs, the trap snaps shut instantly, usually less than half a second. The guard hairs of each lobe mesh together, forming a bar to prevent the insect's escape, and the hapless prey is confined between the lobes. The insect's effort to free itself further irritates the trap, causing the lobe to close more tightly with a powerful force. This pressure sometimes crushes a soft-bodied insect prey.

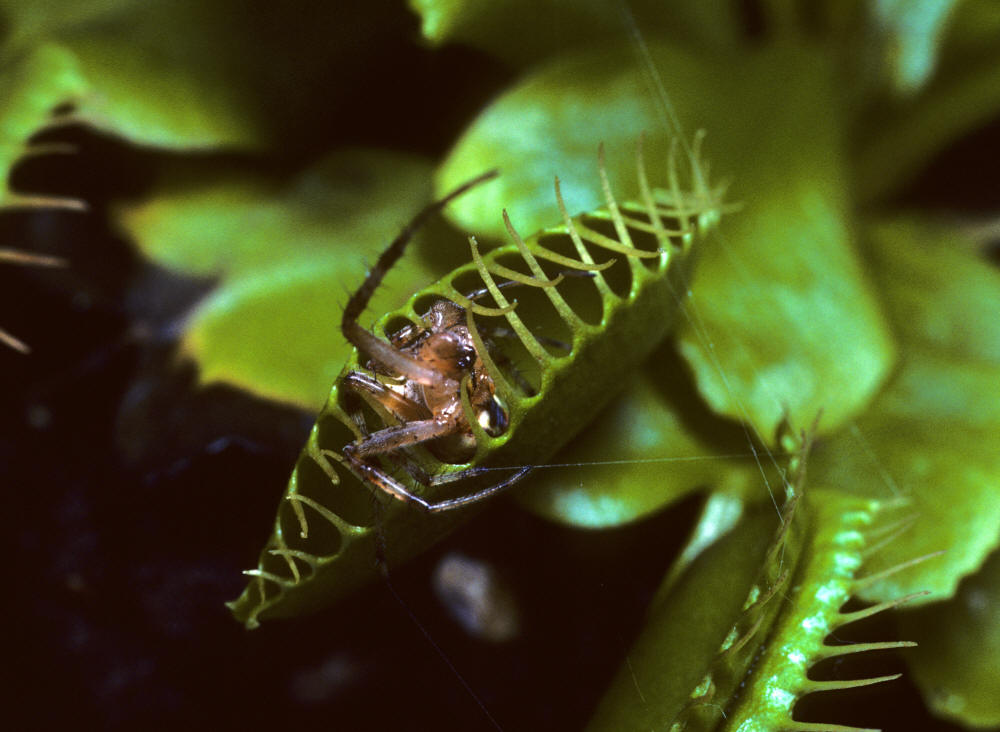

Venus

flytrap and a spider. In nature, flies and spiders are among the most commonly

trapped prey for the plant.

Venus

flytrap pinching a freshly caught wasp.

Multi-exposure photography showing a swift trap leaf closure. Note that the

marginal spines (guard hairs) of the two lobes quickly form a retentive bar to

prevent the prey's escape.

A cross

section of the trap of a Venus flytrap (left) immediately after trap closure.

Note that initially there is a large space inside the trap. As the trap

continues to close more tightly, the space in the trap cavity gets smaller and

smaller, often crushing the trapped insect to death.

A Venus

flytrap catching a fly.

Clock-wise

from upper-left: A fly enters an open trap; the moment the trigger hairs are

touched twice, the trap snaps shut; the marginal spines intermesh to form a bar

to prevent insect escape. Lower-right: Two days later, the lobes are tightly

sealed and the digestion is taking place. Note the pressure of the lobes is

strong enough to crush a soft-bodied insect.

The moment an insect brushes one of the trigger hairs the second time, the trap snaps shut, incarcerating the victim. The trap lobes continue to close more tightly, exerting pressure on the trapped insect. Eventually, the digestive juices fill the trap cavity, digesting the victim. When the absorption of nutrients is complete, the trap opens slowly, revealing the skeleton of the consumed victim.

As the two lobes are tightly sealed, the trap becomes filled with digestive juices from the digestive glands and the trapped animal begins to dissolve. The trap remains closed during the digestive process, which may last for a week to ten days depending on the size of the prey. After all the nutrients of the victim are absorbed by the plant, the trap slowly opens. Inside the now dry trap is the remains of the consumed insect prey. Wind and rain will clean the lobes, and the trap is ready again for its next meal. A single trap is usually capable of repeating this process only a few times during the life of the trap. After that it becomes insensitive to stimulation and dies away. New trap leaves are constantly sprouting from the rosette center of the plant during the growing season of spring through fall.

A back-lit

image of a closed trap showing the shadow of a fly submerged in the digestive

juices.

When a trigger hair is stimulated by a piece of wood - or a finger - the trap also snaps shut. In this case, however, the trap opens the next day, since the plant did not find any nutritious object inside. It is known that, in order to close the trap, two stimulations are necessary: Either two different trigger hairs must be stimulated, or a same hair must be stimulated twice, to trigger the trap closure. This is a plant's clever way of making sure that the prey is well situated in the center of the trap before firing the trap. This also reduces a false alarm by wind blown debris. Considering the enormous amount of energy that is needed to close the trap - for a tiny plant - the Venus flytrap cannot afford too many misses.

A vigorous

Venus flytrap plant growing in the native North Carolina habitat. In July.

In the months of May through June, many white flowers bloom at the top of a tall flower stalk rising from the rosette center of the plant. The tall stalk provides a safe distance for the pollinators from the deadly trap on the ground. Seeds mature by mid-summer in their natural habitat, and tiny Venus flytrap babies are produced by the end of fall. It takes three to four years for the seedlings to reach a flowering age.

The elegant,

white blossoms of the Venus flytrap. In North Carolina, the blossoms start in

early June.

The flower

has five petals and five sepals. Greenish veins run through the white petals. A

flower typically opens for a few days. A slender flower stalk usually bears 10

to 15 flowers at the top (right).

Jet-black,

pear-shaped seeds of the Venus flytrap, measuring 1 mm in length. (The

background scale in the photograph is 2 mm.)

One-week old

babies of the Venus flytrap.

A new leaf

sprouting out of the rosette center of the plant (left), and a new trap about to

open. Note the marginal spines which are starting to unfold.

Fully

matured traps of the Venus flytrap, with attractive bright red margins.

A

transplanted population of the Venus flytrap in the Florida panhandle, in May.

A Venus

flytrap imprisoning a passer-by.

INTRODUCTION

PITFALL TRAPS FLYPAPER

TRAPS SNAP-TRAPS

SUCTION TRAPS VENUS

FLYTRAP SUNDEWS

PITCHER PLANTS COBRA

PLANT BUTTERWORTS

BLADDERWORTS

Carnivorous

Plants Story - Copyrighted Material

Copyright (c) 2013 by Makoto Honda. All Rights Reserved.

Email: mhondax@gmail.com

__________________

For

a young audience, click

here for

"Eaten Alive by Carnivorous Plants" by Kathleen J. Honda & Makoto Honda